When Scottish-American naturalist, John Muir wrote: “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings, nature’s peace will flow into you as the sunshine into the trees. The winds will blow their freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves”, he tendered an idyll of escapism that only a few years earlier Norwegian poet and playwright, Henrik Ibsen, had immortalised as ‘frilufstliv’. Describing a man holed up in the mountains, wrestling with an existential crisis, Ibsen’s poem, På Vidderne, was noted as the first piece of literature in Norwegian history to introduce the word friluftsliv. He penned:

“In the lonely seter cottage

My abundant catch I gather;

There is a hearth, a stool, a table,

friluftsliv for my thoughts.”

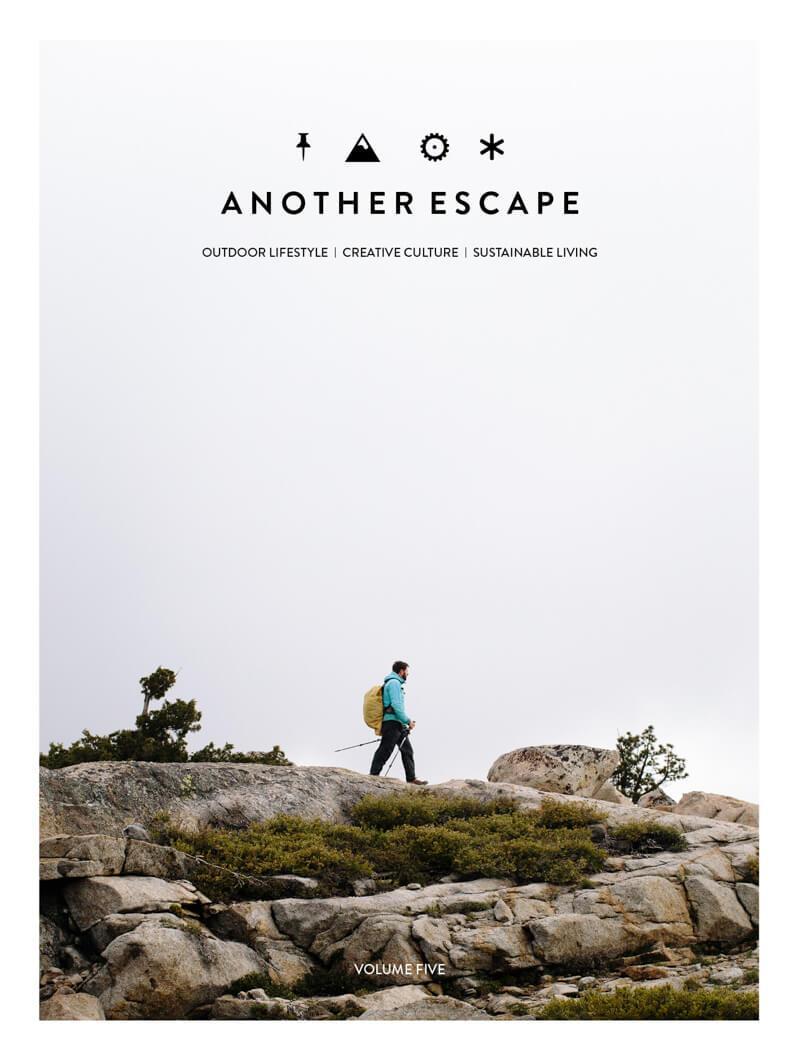

Both sojourners of the 1800s, Muir and Ibsen, strangers separated by the barrelling Atlantic, had inadvertently found commonality in nature. But it was Ibsen’s fellow countrymen and women who took the concept of tethering one’s own soul to the outdoors from a few solitary endeavours to a cultural legacy. Bordering Sweden, Finland and Russia, with a ragged flank that disappears into the pitted bed of the Norwegian sea, Norway is a slender, arcing spool of craggy peaks, vaulting waterfalls, mirrored lakes and fjords, and woolly forests. To the west, the landscape is carved out by glaciers, with the abrupt slopes of the Scandinavian mountains towards the North Sea. Numerous corridors of valley connect this raw, imposing topography to the pine and spruce-carpeted hills of the east. And while the north is characterised by fjords, mountains, vast snowfields and some of Europe’s largest glaciers, the south is a gradation of urban living, agricultural lowlands, fells and docile coastal living.