It was in an in-flight magazine that I first learnt about Ushguli, a community of four beautiful and remote Georgian mountain villages on the border of Russia, high in the Caucasus Mountains and untouched by mass tourism. Nestled in the Upper Svaneti UNESCO World Heritage Site, Ushguli is the highest constantly inhabited settlement in Europe and, according to the article’s supplementary imagery, comprises rustic, medieval, old stone buildings theatrically set upon a backdrop of snowcapped peaks. Tantalised, I read on, and before long a wild plan had begun to form in my mind. I spent the rest of the flight trying to convince my wife, Faye, that it would be a good idea to join me on horseback – despite her having never ridden before – as I attempt to run the 65-kilometre hiking route, through hidden settlements, towering peaks and rocky outcrops, from the highland townlet of Mestia to Ushguli. She wasn’t convinced.

Eight months later, I was on my way to northern Georgia. However, not only had I failed to recruit Faye, but none of my usual adventure buddies were able to join me either. It had become a solo, self-supported trip, the prospect of which I’d initially found quite daunting, especially having read about bears and wolves free roaming the Georgian wilderness. But after months of preparation, both mental and physical, I was ready. More than that, I was excited.

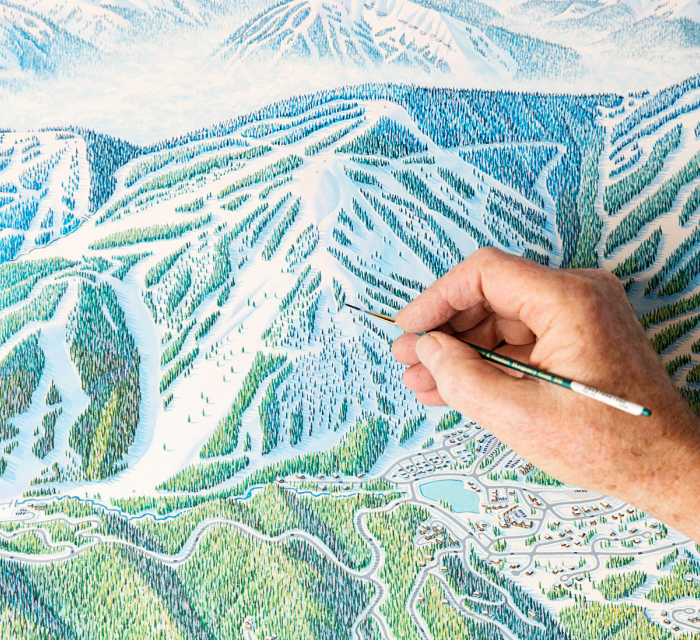

I had devised my running route from a couple of Soviet-era maps I’d picked up on eBay, and plotted my way from Mestia to Ushguli, adding an optimistic extension to the route, continuing on after Ushguli up the Latpari pass, climbing above 3,000 metres, before looping back round to Mestia. According to my plan, the whole route would take me three days to cover 120 kilometres – a day for each leg of the route – and from my research, it appeared that completing the journey from Mestia to Ushguli in a single day would be a record-breaking speed for that distance. I planned to stop in mountain villages each night and try to find a place to stay – I’d heard that many locals use their homes as unofficial guesthouses – which saved me having to carry the extra weight of my camping gear, but also narrowed down my route options significantly.

My flight took me into the city of Kutaisi, and from there I caught a local bus – a converted Mercedes-Benz Sprinter van, rusty and well used, but with a tarted up, gaudy interior with overly plush seating and religious iconography sellotaped to the dashboard. Over the next five hours, as the driver hurtled along the steep, winding roads, I stared out the window as the scene changed from the crumbling facades of Soviet-style apartment blocks to rural villages lost in time, tumbling waterfalls and crystal blue lakes, and the rocky peaks of the Caucasus Mountains. With each stomach-churning hairpin bend, the mountains drew closer, and my anticipation and excitement mounted until finally I arrived in Mestia and my adventure had truly begun.