In Scotland there once was a great forest that stretched from the far reaches of the Scottish Highlands down into the Lowlands. These vast woodlands were alive with a rich diversity of flora and fauna, in which wolves roamed, bears played, and lynxes shuffled through the vibrant undergrowth. However, today the Caledonian Forest has retreated to less than two per cent of its former range and has splintered into small woodland remnants scattered amongst the moors, glens and lochs, losing many species that once called Scotland home. Despite the debate over the Myth of Caledon – whether the forest depleted at man’s hand or nature’s, or both – the slithers of forest remaining today are under threat.

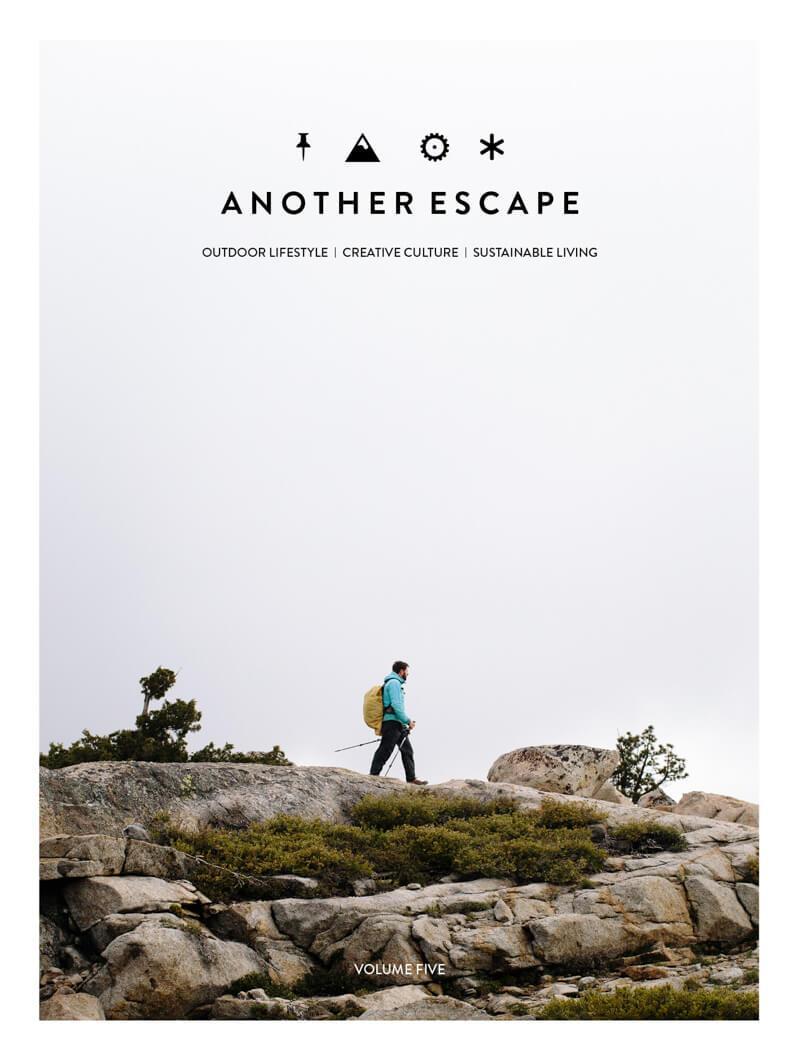

In the heart of the Scottish Highlands lies the magnificent Glen Affric, considered by many to be the most beautiful glen in Scotland. Glen Affric runs for 30 miles from the rugged, snow-laden mountains and barren moors in its eastern reaches, following the River Affric to a beautiful pinewood forest, one of the last Caledonian Forest remnants. There, the rich tapestry of colours and textures, of towering Scots pines, birches, aspens, rowans, willows, alders, all sprouting from a carpet of juniper, heather and bilberry, is breathtaking. Amongst the patchwork of evergreens and deciduous trees live rare biota who rely on this environment.